Patient Resources

Your Knee

Anatomy of the Knee

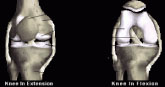

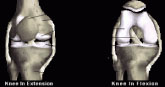

The bones of the knee, the femur and the tibia, meet to form a hinge joint.

The joint is protected in front by the patella (kneecap). The joint is cushioned

by articular cartilage that covers the ends of the tibia and femur, as well as

the underside of the patella. The lateral meniscus and medial meniscus are

pads of cartilage that further cushion the joint, acting as shock absorbers

between the bones.

The bones of the knee, the femur and the tibia, meet to form a hinge joint.

The joint is protected in front by the patella (kneecap). The joint is cushioned

by articular cartilage that covers the ends of the tibia and femur, as well as

the underside of the patella. The lateral meniscus and medial meniscus are

pads of cartilage that further cushion the joint, acting as shock absorbers

between the bones.

Ligaments help to stabilize the knee. The collateral ligaments run along the sides of the knee and limit

sideways motion. The anterior cruciate ligament, or ACL, connects the tibia to the femur at the center of the

knee. Its function is to limit rotation and forward motion of the tibia. A damaged ACL is replaced in a procedure

known as an ACL Reconstruction. The posterior cruciate ligament, or PCL (located just behind the ACL) limits

backward motion of the tibia.

These components of your knee, along with the muscles of your leg, work together to manage the stress your

knee receives as you walk, run and jump.

ACL Reconstruction

The ACL (Anterior Cruciate Ligament) is a ligament in the center of your knee

that becomes damaged when twisted too far, such as in a skiing injury. ACL

reconstruction is performed using a combination of open surgery and arthroscopic

surgery.

The ACL (Anterior Cruciate Ligament) is a ligament in the center of your knee

that becomes damaged when twisted too far, such as in a skiing injury. ACL

reconstruction is performed using a combination of open surgery and arthroscopic

surgery.

This arthroscopic view shows a healthy ACL that is firmly attached to the femur and

tibia.

Before the ACL reconstruction process begins, your surgeon will examine your knee

arthroscopically, and repair any additional damage to the knee, such as a torn meniscus, or worn articular

cartilage.

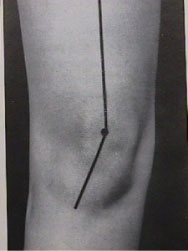

Reconstruction of the ACL begins with a small incision in your leg where small

tunnels are drilled in the bone.

Reconstruction of the ACL begins with a small incision in your leg where small

tunnels are drilled in the bone.

Next your new ACL is brought through these tunnels, and then secured with a

staple and buckle system.

As healing occurs, the bone tunnels fill in to secure the tendon.

Total Knee Replacement

Arthritis of the knees can be mechanical (osteoarthritis) in which the

surfaces of the knee gradually "wear out." This may be due to age,

angular deformity or old fractures. Systemic arthritis such as rheumatoid

arthritis or gout affects the synovium (the membrane tissue in the joint

that normally lubricates the joint), becomes pathologic and the surface

of the joint is destroyed.

Arthritis of the knees can be mechanical (osteoarthritis) in which the

surfaces of the knee gradually "wear out." This may be due to age,

angular deformity or old fractures. Systemic arthritis such as rheumatoid

arthritis or gout affects the synovium (the membrane tissue in the joint

that normally lubricates the joint), becomes pathologic and the surface

of the joint is destroyed.

In either case when the surface of the joint is worn away, at a certain

point in time walking and activities of daily living become very difficult.

Standardized treatment such as weight loss, anti-inflammatory medication, braces, orthotics, steroid

injections, physical therapy, etc. are all tried and if effective that is fine.

In many cases, however, despite the above non-surgical treatments, functional limitations persist. Most

people who are considering knee replacement are limited to walking less than three to six blocks, or less than

15 to 20 minutes. They have difficult time getting up out of a chair. They have rest pain. They are taking antiinflammatory

medication and/or pain medicine on a regular basis and the pain is generally progressive.

It is important to realize that a knee "replacement" is actually just a "resurfacing" of the knee joint. The femur

or thigh bone is covered with a metal covering and plastic is placed on the tibia so that instead of irregular

arthritic surfaces, one has metal and plastic articulating which produces a smooth non-patent surface. In most

cases the undersurface of the kneecap is also replaced with a plastic surface so that this articulates with the

femoral surface.

Knee replacements have been done since the early 1970s and our most recent designs appear to have 85%

to 90% survival at twenty years.

The actual procedure involving knee replacement involves either general or epidural anesthesia with a four to

six day hospitalization. The surgery itself takes between 1-1/2 and 2-1/2 hours. In most cases patients donate

two units of autologous blood to be used in the postoperative period. Weight-bearing begins immediately the

first postoperative day. Patients usually use a walker for a period of one to two weeks, going to crutches and

then a cane. People are off all walking aids anywhere from three weeks to two months.

Success rates in knee replacements are approximately 90% with 10% not doing as well. This can be due

to either stiffness or ache or swelling in and about the knee. The most significant complications, aside from

general medical complications (heart and lung) involve infection of the prosthesis. If this occurs, in some

cases the prosthesis can be saved and the patient taken back to the operating room, the knee irrigated

with antibiotic irrigation and then be on antibiotics. In some cases if this does not respond, then the entire

prosthesis must be taken out and antibodies given for six weeks and then another attempt at re-implantation

of the of the prosthesis must occur. In an extremely small percentage of cases, conceivably if the infection

could not be controlled, then one is left a knee fusion in which the femur and tibia are fused in one bone.

Activities after knee replacement that should produce no difficulty are simple walking, bicycling, golfing,

and swimming. The prosthesis is not designed form impact loading sports such as skiing, basketball, or

racquetball. People have been known to play doubles tennis with bilateral knee replacements.

Cartilage Repair

About Cartilage

About Cartilage

Normal knee function requires a smooth gliding articular cartilage

surface on the ends of the bones. This surface is composed of a thin

layer of slippery, tough tissue called hyaline cartilage. This cartilage also

acts to distribute force during repetitive pounding-like movements such

as jumping or running.

Injured Cartilage

A severe knee cartilage injury can radically change an active adult's

lifestyle. Symptoms such as locking, catching localized pain and swelling

often affect your ability to work, play, and even perform normal activities.

A cartilage lesion appears as a hole or divot in the cartilage surface.

Since cartilage has minimal ability to repair itself, even shat may seem

like a small lesion (ranging from the size of a dime to a quarter), if left

untreated, can hinder your ability to move free from pain, and cause

deterioration to the joint surface.

Treatment with Autologous Chondrocyte Implantation (ACI)

Although cartilage in unable to repair itself on its own, advanced FDA-approved technology allows cartilage

cells, know as chondrocytes to be harvested from your knee and cultured and multiplied. The fresh

chondrocytes are then reimplanted in your knee and cause hyaline cartilage to regenerate. This biological

repair is known as ACI. When you successfully complete ACI and rehabilitation, you should be able to resume

all normal activities, including sports.

ACI, also known as carticel treatment, restores the articular surface and regenerates hyaline cartilage without

compromising the integrity of healthy tissue or the subchondral bone.

Carticel has demonstrated important benefits in patients with a type of lesion called a femoral focal lesion. If

your orthopedic surgeon has determined that you have this type of lesion, then carticel may be an appropriate

treatment option.

The procedure consists of two steps. The first is the harvesting of some healthy cartilage from you knee

through and arthroscope. This sample of cartilage is used to create new chondrocytes, which take 3-4 weeks

that are then reimplanted in your knee.

The second step is the reimplantation of the cultured chondrocytes, or Carticel. This procedure is done

through an arthrotomy, and is depicted below.

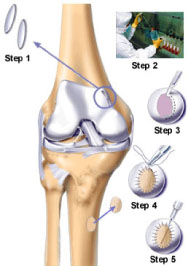

Implantation of Carticel

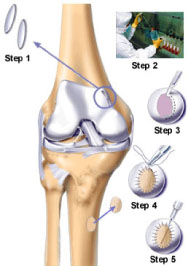

Step 1: An arthroscopic biopsy – First, the surgeon examines your knee through an arthroscope – a small

device that allows the doctor to see into your knee joint. If a lesion is detected, a tiny biopsy of healthy

cartilage tissue will be removed.

Step 2: Cell culture processing – The cartilage sample is then sent to Genzyme Tissue Repair (GTR), where

it is cultured. Cell culturing takes about 4-5 weeks, during which time your cells multiply significantly. About 12

million cells will be supplied to your surgeon at the time of your operation.

Step 3: A surgical procedure is performed, and the damaged cartilage is removed.

Step 4: Periosteum, skin that covers the bone, is sutured over the prepared defect.

Step 5 Surgical implantation – The cultured cells are then implanted into the lesion. Here, the cells may

continue to multiply and intergrate with surrounding cartilage. With time, the cells will mature and fill-in the

lesion with hyaline cartilage.

Post-Operative rehabilitation

To derive maximum benefit from ACI, you should adhere strictly to the

personalized rehabilitation plan recommended by your physician. This

will include progressive weight bearing, range of motion, and muscle

strengthening exercises, which may begin as early as the day after

surgery.

To derive maximum benefit from ACI, you should adhere strictly to the

personalized rehabilitation plan recommended by your physician. This

will include progressive weight bearing, range of motion, and muscle

strengthening exercises, which may begin as early as the day after

surgery.

Chondromalacia

Chondromalacia is a diagnosis referring to damage, and subsequent

pain, to the cartilage under your kneecap. It can be caused by several

factors, and produces discomfort with such activities as walking up and

down stairs, kneeling, squatting, or getting up from a seated position. It

can occasionally produce swelling in the knee and a sensation of giving

way or "catching" ("locking").

Chondromalacia is a very common problem and is directly related to the

amount of pressure between the kneecap and the femur bone beneath

it. This pressure is normally 2-3 times your body weight when simply

descending stairs - one can imagine the magnitude of the pressure

when running! All the following suggestions and treatments are directed

at decreasing the pressure between the kneecap and the underlying

femur.

at decreasing the pressure between the kneecap and the underlying

femur.

The usual precipitating cause of pain in the patient with chondromalacia

is either trauma (an injury such as a fall on the knee or a car accident)

or a developmental abnormality (malalignment) of the knee, which

may predispose a patient to kneecap pain. Some patients suffer from a

kneecap that repeatedly dislocates (usually towards the outside of the

knee), which not only causes pain, but buckling of the leg and damage to

the undersurface of the kneecap.

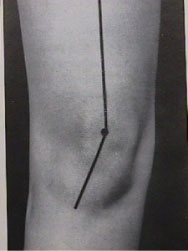

There is a "normal" relationship between the thigh muscle, the patella,

and the point of attachment of the patellar tendon. This is described by

the quadriceps angle (q-angle). In those people in whom the q-angle is

larger than normal, there is a greater tendency for the kneecap to track

abnormally in the groove on the front of the femur with knee bending,

leading to increased pressure in certain parts of the kneecap-femur joint.

|

For Our Patients

Existing patients may utilize these convenient links to access forms, educational materials and manage their accounts.

Medical Questionnaire

Patient Forms

Convenient, Online

Patient Forms Are

Coming Soon!

Pay My Bill

INSURANCE PROVIDERS WE PARTICIPATE WITH:

Commercial

Blue Cross/Blue Shield

DMBA

HMA

HMAA

HMSA PPO & HMSA HMO

MDX

UHA

Government

Medicare

Medicaid

OHANA/Wellcare

Triwest/Tricare

UHC- Medicare Advantage

Other

Workers Compensation

No-Fault

|

The bones of the knee, the femur and the tibia, meet to form a hinge joint.

The joint is protected in front by the patella (kneecap). The joint is cushioned

by articular cartilage that covers the ends of the tibia and femur, as well as

the underside of the patella. The lateral meniscus and medial meniscus are

pads of cartilage that further cushion the joint, acting as shock absorbers

between the bones.

The bones of the knee, the femur and the tibia, meet to form a hinge joint.

The joint is protected in front by the patella (kneecap). The joint is cushioned

by articular cartilage that covers the ends of the tibia and femur, as well as

the underside of the patella. The lateral meniscus and medial meniscus are

pads of cartilage that further cushion the joint, acting as shock absorbers

between the bones. The ACL (Anterior Cruciate Ligament) is a ligament in the center of your knee

that becomes damaged when twisted too far, such as in a skiing injury. ACL

reconstruction is performed using a combination of open surgery and arthroscopic

surgery.

The ACL (Anterior Cruciate Ligament) is a ligament in the center of your knee

that becomes damaged when twisted too far, such as in a skiing injury. ACL

reconstruction is performed using a combination of open surgery and arthroscopic

surgery. Reconstruction of the ACL begins with a small incision in your leg where small

tunnels are drilled in the bone.

Reconstruction of the ACL begins with a small incision in your leg where small

tunnels are drilled in the bone. Arthritis of the knees can be mechanical (osteoarthritis) in which the

surfaces of the knee gradually "wear out." This may be due to age,

angular deformity or old fractures. Systemic arthritis such as rheumatoid

arthritis or gout affects the synovium (the membrane tissue in the joint

that normally lubricates the joint), becomes pathologic and the surface

of the joint is destroyed.

Arthritis of the knees can be mechanical (osteoarthritis) in which the

surfaces of the knee gradually "wear out." This may be due to age,

angular deformity or old fractures. Systemic arthritis such as rheumatoid

arthritis or gout affects the synovium (the membrane tissue in the joint

that normally lubricates the joint), becomes pathologic and the surface

of the joint is destroyed. About Cartilage

About Cartilage To derive maximum benefit from ACI, you should adhere strictly to the

personalized rehabilitation plan recommended by your physician. This

will include progressive weight bearing, range of motion, and muscle

strengthening exercises, which may begin as early as the day after

surgery.

To derive maximum benefit from ACI, you should adhere strictly to the

personalized rehabilitation plan recommended by your physician. This

will include progressive weight bearing, range of motion, and muscle

strengthening exercises, which may begin as early as the day after

surgery. at decreasing the pressure between the kneecap and the underlying

femur.

at decreasing the pressure between the kneecap and the underlying

femur.